Herring Scrap 38 - The Rule of Three

Back in 2022, before herring scraps went online in this format, I wrote in Herring Scrap 11 about the "rule of three" which can trigger the confidentiality of commercial fish harvests if there are three or fewer fishers or processors participating in a fishery. With a new merger of two Alaska processing giants, this subject gained new relevance this week in Sitka; here I'll give a bit of new information about the Sitka situation before sharing parts of that older writing, about how the Rule of Three has previously been triggered in the Togiak herring fishery.

At the pre-fishery meeting held by ADF&G in Sitka on Wednesday evening, Area Manager Aaron Dupuis indicated that "Because we will have less than three processors this year, I think this is the first time ever in the history of the Sitka Sound Sac Roe herring fishery that because of the number of processors, harvest data will be confidential from this year. That's state law, there's no way around it. Wish it were different sometimes, but harvest data will be confidential this year.”

He's telling us that we'll never know how much herring is caught in Sitka this year, and is referring to ADF&G’s Rule of Three: “Confidential ADF&G commercial fisheries data may be released to the public in summary format. The data must be aggregated in such a way as to reflect at least three entities. Three entities means there must be at least three people; three permits; three vessels (if applicable); and three buyers or processors in the summarized data. This is done to protect individual business activities and fishing locations. The source or type of confidential data dictates the type of entities that must be reflected in the aggregate.” This rule shows up in an ADF&G policy document published by the Division of Commercial Fisheries, the Confidentiality of Fisheries Information Divisional Operating Procedure CF-008; that document is responsive to Alaska Statute section 16.05.815, which in turn (as far as I can tell) is responsive to the information sharing requirements of the federal Magnuson-Stevens Act.

The change in Sitka that brought the processor count down to three or fewer seems seems to have happened in large part because of a major just-announced buyout of OBI Seafoods by Silver Bay Seafoods. This buyout follows last year's buyout of parts of Trident Seafood's operations by Silver Bay Seafoods, as well as the 2020 merger that formed OBI Seafoods by combining Ocean Beauty and Icicle Seafoods. This rapid consolidation has brought most of the processors under the same umbrella, triggering confidentiality of harvest in Sitka's herring fishery for the first time.

The masking of harvest data is a remarkable development for this fishery, especially at a time when the State of Alaska is actively pursuing every loophole they can find to open the doors to year-round herring fishing. I don't see any reason to assume that this couldn't become the new normal; it seems very possible that the tonnage of herring taken commercially in Sitka Sound will never be disclosed again.

When I covered this topic in 2022, I explained that I felt sure that the law wasn't established with extreme consolidation at the processor level in mind - surely it was meant to protect confidentiality for smaller operators in smaller fisheries, right? But here we are: the fishery in Sitka Sound will take more than fifty million herring out of Sitka Sound this month, and the total amount won't need to be disclosed. Doesn't seem right to me, but I'm not an antitrust lawyer.

That mostly covers what I wanted to say about this week's Alaska herring scandal.

Now I want to share a slightly edited version of the back half of herring scrap 11. It has to do with the herring fishery in Togiak (in Bristol Bay, just north of the Aleutian chain, part of the Eastern Bering Sea), which is the first large scale sac roe herring fishery where I noticed the rule of three being triggered.

Three is an allegedly magic number, and with magic comes rules, and so there are many Rules of Three out there, only one of which is the subject of this scrap.

Back in 2022, a book came out called Alaska Herring History by James Mackovjak. I didn't like it—I found it simplistic, under-referenced, and overly deferential to ADF&G. But one section stood out to me: the history of the Togiak roe herring fishery. It raised questions—especially about the Rule of Three and industry consolidation—that I hadn’t considered before.

Some background: In 1978, when the Southeast Alaska roe herring fishery went Limited Entry, creating an exclusive entitlement among 50 seine permit holders, the same thing didn’t happen up in Togiak. For the next couple of decades, that fishery must have been strictly bonkers—open to both gillnetters and seiners, with hundreds of boats showing up. A look at the CFEC registry shows that in 1997, there were 421 G01T (“HERRING ROE, PURSE SEINE, BRISTOL BAY”) permits and 748 G34T (“HERRING ROE, GILLNET, BRISTOL BAY”) permits. While not all of them fished, hundreds of boats were on the water. And that level of participation had been the standard for years.

From there, though, the numbers start to decline. By 2003, participation had dropped significantly—37 purse seiners, 82 gillnetters, and 8 processors. Mackovjak explains how and why:

“As had been done the previous year and would be the norm in the future, the purse-seine fishery was done cooperatively. Constrained by limited markets, processors, to maximize their efficiency, chose the makeup of their purse-seine fleets. This gave them the power, in collusion with fishermen members of the cooperative, to exclude entrants into the fishery. To prevent a recurrence of the massive dumping of herring that had occurred in 2001, both ADF&G and state troopers warned processors and fishermen that anyone responsible for releasing dead herring would be cited for wanton waste.”

The italics are mine for emphasis. The power… in collusion… to exclude. This wasn’t just market forces at play—it was an engineered fleet reduction in the hands of the processors.

Towards the end of his section on Togiak, Mackovjak covers the years 2005-2019 in a single page, referring to them as the final ‘normal’ years of the Togiak roe-herring fishery. But what exactly does normal mean here? He doesn’t point to any major regulatory change at the end of this period—only to temporary disruptions like the pandemic and a market glut. He notes, almost in passing, that “because of low fishery participation, the harvest volume is confidential.”

But here’s the thing: even though participation was low in those years, the harvest wasn’t.

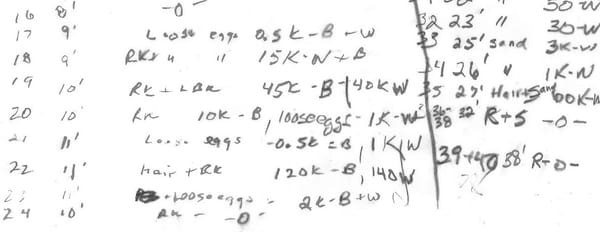

In 2016, the price ($0.06 per pound) and the catch (just under 30 million pounds) were nearly identical to 2003, but the number of participants had collapsed—just 17 seiners and 3 gillnetters. Those seiners were selling to only 4 processors, whereas there had been 8 in 2003. That year, the Rule of Three was triggered on the gillnet side, making their harvest data unavailable. By 2019, the total harvest had reached a record 45 million pounds—secured by just 20 permit holders on behalf of 4 processors.

Togiak didn’t see a collapse in the fishery—it saw a processor takeover. There was no formal regulatory cap on participation, no mandated fleet reduction. Just an industry-driven consolidation of involvement, without - at least for many years - a commensurate reduction in catch.

The Rule of Three was triggered in full in Togiak in 2020, 2021, 2022, due to fewer than 3 processors participating.

There are no harvest numbers, no prices for the Togiak herring fishery in those years. Instead, all we know is that in 2021 there were 2 buyers for seined herring with 8 permit holders fishing for them - just half of the participation that brought in a record harvest just two years prior.

And then for 2022, the “2022 Togiak Herring Season Summary” offers a tease of information: “Specific harvest numbers are confidential but the total harvest was less than 25% of the 52,086 ton purse seine guideline harvest level.” That sounds to me like they caught something not too much less than 13,021 tons - plenty of herring, and not much less than “normal”. That report also suggests that the two processors which operated are Silver Bay Seafoods and OBI Seafoods (the same OBI Seafoods that has just been bought out by Silver Bay Seafoods).

For ADF&G, this collusive consolidation thing appears to be a dream scenario: the first words of the Bristol Bay Herring Management Plan (5AAC 27.865) are: “When managing the Bristol Bay commercial herring fishery, the primary objectives of the department are to prosecute an orderly and manageable fishery”. In their 2020 Bristol Bay Area Annual Management Report - the last such report available - ADF&G indicates a total embrace of the change: “For at least the past decade, the seine fleet has been composed of processor-organized cooperatives. During the 2020 season, management staff allowed long duration purse seine openings across a large area of the district and let processors limit harvest for their individual fleets based on processing capacity.”

The Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission doesn’t mind it either; at the 2018 Board of Fisheries meeting about Bristol Bay Finfish, the CFEC submitted a document (RC39) called CFEC Permits and Estimates of Gross Earnings in the Togiak Sac Roe Herring Purse Seine and Gillnet Fisheries, 1983-2017. In it, they acknowledge the modern arrangement: “Since 2001, processors have done business exclusively with cooperatives formed within the purse seine fleet. The arrangements vary, but typically a processor selects a limited number of seine vessel operators to deliver herring to them. Each cooperative may consist of three individual vessels and/or permit holders. The ex-vessel proceeds are then split equally among the permit holders or vessel owners present for each opening. Since this information is not captured on ADF&G fish tickets, the exact arrangements of cooperatives are not known with any degree of certainty. It is assumed that this type of business arrangement will continue for the foreseeable future due to depressed market conditions for sac roe herring and thin economic margins specific to Togiak herring.”

That document includes a breakdown in local vs non-local participants in the fishery; It appears that there are no longer locals involved in that fishery.

****

Togiak, like Sitka, has seen a big bloom in assessed biomass in the last decade, and with that comes a much higher allowed harvest. Whether that bloom is for reasons biological, bureaucratic, or methodological, I don’t know, because there is no data whatsoever to look at and no indication of substantial study. Meanwhile, there hasn't been a fishery there for the last couple years.

But what happens if in one or five or ten years, the market is right, and the biomass is high, and ~the power… in collusion… to exclude~ is still in the hands of processors? Could 25,000 or 50,000 or 70,000 tons of herring be caught without the numbers being released? It seems like there is every reason to believe that could happen. That’s a new possibility, the result of growing power at the processor level. I don’t think that’s what the Rule of Three was established to allow. And as it turns out, I don't think it's what the processors have in mind as the best use for Togiak herring. There's one more twist on this magic carpet ride.

The herring which spawn in Togiak migrate into the areas accessed by the pollock trawlers later in the summer.The pollock trawl fishery which operates in the Eastern Bering Sea (EBS) are limited to a take of 1% of the estimated herring population as bycatch. If they exceed that while fishing in the so-called “Herring Savings Areas”, then they need to shut things down. This happened in 2020, when the early-summer pollock “A Season” reached the 1% limit and triggered a closure to the HSA’s for the late-summer “B Season”.

The trawl fleet did not accept the penalty. Instead, they declared (in a letter on June 1) that “herring is a constraining species for our fishery”, and requested that the penalty be waived on an “emergency” basis and that the herring allowance be doubled to 2% (5064 metric tons). In a sort of bycatch blackmail, the trawlers claimed that if they fish outside of the Herring Savings Areas they will be unable to avoid bycatch among other valued species (most notably Chinook salmon). Their letter to the North Pacific Fishery Management Council (NPFMC) made it clear that abundance and biodiversity are barriers to success for the fishery.

In response, the NPFMC Advisory Panel held extensive discussions about this “emergency”. As it became clear that the public and many members of the AP wanted to see the 1% rule stay intact, the chairs of the AP - all three of whom have interests in the pollock trawl fishery - avoided a doomed vote on the matter and sent it on to the Council. The Council, in turn, and in consultation with ADFG, deepened the procedural subterfuge and dodged accountability by re-casting the request for increased bycatch as a question for “in-season management” authority - which they granted. During that meeting, ADF&G Deputy Commissioner Rachel Baker was asked how much bycatch ADF&G would tolerate, and Baker indicated that ADF&G would likely be fine with 2 or 3% (5064/7596 tons) of bycatch. And so the pollock trawl fishery was able to keep going that year.

But remember that thing about how ADF&G is suddenly reporting twice as much biomass as they ever have before? That might benefit the seiners tomorrow, but it is benefiting the trawl fleet now. The Federal Register Vol 87, No 41, p 11641 from Wednesday March 2nd, 2022, had the scoop: “Pursuant to § 679.21(e)(1)(v), the PSC limit of Pacific herring caught while conducting any trawl operation for BSAI groundfish is 1 percent of the annual eastern BS herring biomass [I love seeing the phrase “BS herring biomass” in the Federal Register, by the way]. The best estimate of 2022 and 2023 herring biomass is 381,876 mt. This amount was developed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game based on biomass for spawning aggregations. Therefore, the herring PSC limit for 2022 and 2023 is 3,819 mt for all trawl gear”. Thus, unfished Togiak herring directly benefit the trawl fishery.

It's worth noting here that the CEO of Silver Bay Seafoods, Cora Campbell, used to be the ADF&G commissioner (2010-2014). In the years in between, she worked for a different organization, Siu Alaska Corporation, a for-profit subsidiary of the Norton Sound Economic Development Corporation which operates a number of trawl vessels operating in the Eastern Bering Sea. She has also held a seat on the NPFMC - the guiding body for the Eastern Bering Sea trawl fishery - in recent years.

What the Rule of Three allows to happen is that once the consolidation of involvement – the power… in collusion… to exclude – reaches a certain point, there is a mechanism in place allowing catch and price to become invisible to outside observers.

In Sitka, that means no one outside the industry will know how much herring is taken, what price is paid, or how the fishery is really operating. In Togiak, it means herring that could be caught in a sac roe fishery instead swell the estimated biomass, directly inflating the bycatch allowance for the pollock fleet.

The more that processing power is consolidated, the fewer eyes there are to see what happens, and the easier it becomes to justify future decisions based on numbers no one can verify.

Maybe three is a magic number after all.