Herring Scrap 37: Alaska Herring Bureaucracy Roundup

You haven't heard from me for a while. I want to tell you about a series of meetings that offered dispiriting conclusions to the threads that I've described regarding Herring Revitalization Committee (which I talked about in scrap 23 and scrap 28 and, sort of, scrap 36), the whole thing about the Unfished Biomass simulation study (which I covered in scraps 27, 29, 30, and, sort of, 33 and 34), and the Alaska Board of Fisheries in general (scrap 19, and, sort of, 35). It's been a busy time for herring bureaucracy in Alaska, and I feel I owe you and the rest of the internet an update. The procedural action that I'll describe mostly took place in two meetings - the Southeast Alaska Board of Fisheries meeting covering finfish issues, which took place in Ketchikan at the beginning of February, and the recent Statewide Board of Fisheries meeting which took place last week in Anchorage. I was there in person for the Ketchikan meeting; I took in the Anchorage meeting online. I'll also share a bit about another meeting - the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute's last conference - at the end.

The Southeast Alaska Board of Fish meeting was among three or four near-simultaneously held meetings across Alaska at the start of February (see also: Federal Subsistence Board, North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, Pacific Salmon Commission) which collectively and variously define and administer access to and impact of different user groups to a number of resources, lifeforms, and economies in this part of the world. It seemed like everyone had somewhere else to be.

As it turned out, there were still many of us there in Ketchikan collectively presenting myriad arguments for herring protection, precautionary management, movement towards tribal co-management, and the need to protect the customary and traditional harvest of herring roe on branches at the places best suited for it. I was there in hopes that the Board of Fisheries process might somehow be moved by some of the various concerns I've expressed or shared here lately and all that everybody else had to say. Ultimately, they weren't; it was a typically disappointing, sadly unsurprising set of results.

Rubber Stamping the ADF&G Proposals

In the end, of the 20 herring proposals, it was only the three proposals submitted by ADF&G which were passed by the board. This matched the profile of historic action at the board of fish – the scholarship on the board process in Krupa et al 2019 demonstrates that proposals brought by ADF&G, other Government agencies, or the Board of Fisheries itself, are vastly more likely to be affirmed by the Board of Fisheries than proposals brought by individuals, tribes or villages, or other associations. In this sense, the findings suggest, the Board of Fisheries presents as a public process but behaves like an administrative process.

Two of those ADF&G-submitted proposals which passed will nominally improve the situation for herring in Southeast Alaska - now, the commercial fishery will be allowed up-to-15% of the herring biomass in a place per year, which is indeed an improvement of the up-to-20% standard of recent decades. The proposal that effected that change in Sitka Sound was ADF&G's Proposal 171 – the same proposal that was written in order to put the Simulation Study to Estimate Unfished Biomass of Sitka Sound Pacific Herring into regulation.

In advance of and during the meeting, I particularly tried to get board members (via emails, conversation, and public written comment) to engage with the idea that they should apply a higher threshold (below which fishing can't occur) to correct for the faulty time series used by that Simulation Study. They did not engage with that idea, didn't engage with the Simulation Study at all. The Department volunteered no information about the Simulation Study and they were not asked questions about it by the Board. When the Department scientists offered their presentation, the biometrician who served as lead author of the study sat in silence at the front of the room, unintroduced, available for unasked questions on a subject that hadn't been presented.

Undiscussed: the study designed to emplace a critical metric for the application of maximum sustainable yield in Sitka Sound! It provides the framing for how both low and high abundance are understood. The study - its sources, its findings, its assumptions - went unaddressed. One board member indicated that he'd tried to read it, but fixated pointlessly on the Canadian examples cited in the paper and didn't really address the means or the ends of the study. In the end, the Board passed the proposal without engaging in so-called science that led to the Department's determinations about threshold levels and abundance states. Generally, they didn't ask questions of those of us advocating for herring protection, either - they let us say whatever we had to say, so long as we were snappy about it, and in almost all cases no questions followed.

It reminded me of what the Alaska Supreme Court justices ruled in the Sitka Tribe of Alaska vs State of Alaska case about herring a few years ago: people like judges and Board of Fisheries members shouldn't be expected to understand technical/scientific things like ADF&G's Simulation Study. Expertise is an armored island.

Further to this point, I asked two of the biometricians - one by email and one in person - to take the time to chat with me about my concerns. The first didn't reply, and the second declined to meet, telling me that I should talk to the Director of Commercial Fisheries instead. I talked to the Director, but he wasn't familiar enough with any of this stuff to meaningfully address my concerns. In the end, there was no opportunity for dialogue that might confront deficiencies in the science, and the junk science got rubber stamped and reified.

Dismissing Tribal Co-Management

What didn't get rubber stamped was a Herring Protectors proposal that ADF&G must "develop a consent-based co-management framework to allow for collaborative management efforts with appropriate local sovereign Tribal Government(s)" when trying to prosecute or develop a herring fishery. Going into the meeting, the Proposal seemed to have a head of steam, having been affirmed by Regional Advisory Committees to the Board of Fish in Upper Lynn Canal and in Sitka. At the same time, the proposal was dead in the water: in the Department's staff comments on the proposal, staff had written that, if passed, "The department would continue to be the sole management entity as the Board of Fisheries (board) does not have the authority to give management authority to another entity or direct the department to co-manage a fishery." If the co-management proposal passed, it would not be put into practice, the Staff comment suggested.

In an effort to make something workable from the idea, Sitka Tribe of Alaska put forward an amendment to Proposal 190. Rather than a consent-based co-management framework as proposed, the Tribe suggested a return to a collaborative framework that had been in place from 2002 until 2009, at which time ADF&G unilaterally withdrew from the agreement. The original agreement had been formed initially via a Memorandum of Agreement and principally defined guided improved communication and participation in processes between the Tribe and ADF&G; it relinquished no control over the fishery and no authority over the science that guides it nor the decisions made. The new version didn't seem like something that the State of Alaska should find terribly threatening, but in the end, I guess they did. ADF&G Commissioner Doug Vincent-Lang - who could not be at the meeting during deliberations because he was on the way to the Pacific Salmon Commission meetings - passed along his remarks on the matter, saying, "I am not willing to agree to sign the proposed MOA with the Sitka Tribe at this time. I believe we can get to the same end by using other means that ensure all users understand management decisions and are equally engaged in research. Again, thank you for your heartfelt discussions, I look forward to continuing them in the future." Thus, Proposal 190, and an amended version to it that STA had submitted, were torpedoed, and the meeting came quickly to a close, with no new threats to herring in Southeast Alaska but no meaningful new protections either.

Making up the Rules

Since I've been following Herring Revitalization Committee closely, I felt quite sure going into the Southeast Board of Fish meeting that some sneaky circumvention of regular process might occur at the Southeast meeting to advance the goals of that committee. I wasn't quite sure what form that subversion of process might take. Now that it's happened, I can tell you how it happened.

The Southeast meeting was technically two Board of Fisheries meetings back to back; the "finfish" meeting - that's where herring discussions belong - directly followed the "groundfish and shellfish" meeting. Those of us there to advocate for herring protection weren't present for the "Shellfish" meeting in the week before herring discussions were scheduled. And so of course, that's where the sneaky circumvention of regular process occurred: Board Member Godfrey - the same Board Member who asked in 2022 how subsistence harvesters attached the herring eggs to their hemlock branches - advanced a "Board Generated Proposal" that had been floated by Herring Revitalization Committee members to radically expand the entitlement of herring permit holders in Kodiak. It was put forward in Record Comment #25 by Bruce Schactler, and then Member Godfrey advanced it as language for a Board Generated Proposal in Record Comment #67. The short version is that this proposal was designed to allow Kodiak herring sac roe permit holders to fish for 11 months of the year instead of 3.

And so it happened that in the "Miscellaneous Business" section of that "Shellfish" meeting in Southeast Alaska, with nobody in the room to oppose the sudden gesture, the Board voted to put the proposal onto the agenda for discussion one month later at the "Statewide Shellfish, Prince William Sound Shrimp, and Supplemental Issues" meeting in Anchorage, providing an absolute minimum of opportunity for public engagement and appropriate process. Not all Board members were convinced that the proposal met the special criteria for a "Board Generated Proposal" (Is it in public's best interest? Is it urgent? Are regular processes insufficent? Will there be adequate opportunity public comment?)... but it was voted ahead anyhow.

Fast forward a couple weeks: Three days before the public comment deadline for the meeting, I contacted the Resource Protection Department of the Sun'aq Tribe of Kodiak. They hadn't been informed about any of this. A couple days later, an underwater fiber cable was damaged in the Gulf of Alaska, and the ADF&G / Board of Fisheries website went down for days. A week later, the meeting was happening, and the proposal was up for discussion.

At the meeting, a second group of permit-holders, the Kodiak food&bait permit holders, felt like this new fishery would encroach on their doings; the Kodiak Food and Bait Herring Association suggested substitute language in Record Comment #37 which was more favorable to their group; meanwhile, the Kodiak Seiners Association (representing the sac roe permit holders) pushed in their own substitute language designed to overcome legal/regulatory issues identified by the CFEC with the initial proposal - that was Record Comment #38. Finally, maybe an hour before Board Deliberation, Board Member Godfrey published Record Comment #70, featuring final language that had been written by Department staff which incorporated input from those two groups of permit holders as well as the Commercial Fisheries Entry Commission. That final language provided a major expansion of access to the sac roe permit holders while also boosting the allocation for the food/bait crowd.

Before the vote, the Board Chair Marit Carlson Van-Dort complained "There's a level of frustration that I feel like I'm experiencing here because the Board has not been presented at this meeting with any information regarding the status of the stocks, how much biomass we're talking about, how that allocation would be divvied up, what the GHLs would be or how those would be determined. And so I'm reading this and unless I'm steeped and super familiar with herring in Kodiak I don't feel like I have enough information here to make a really good informed decision about this. I appreciate the fact that there's been a lot of work done on this but there's no - essentially, very little information that has come forth from the Department to explain to me numerically, graphically, however it's usually done, to make an informed decision about this." A few minutes later, having been provided with no new information, the proposal was voted into regulation by the Board, 7 in favor, none opposed.

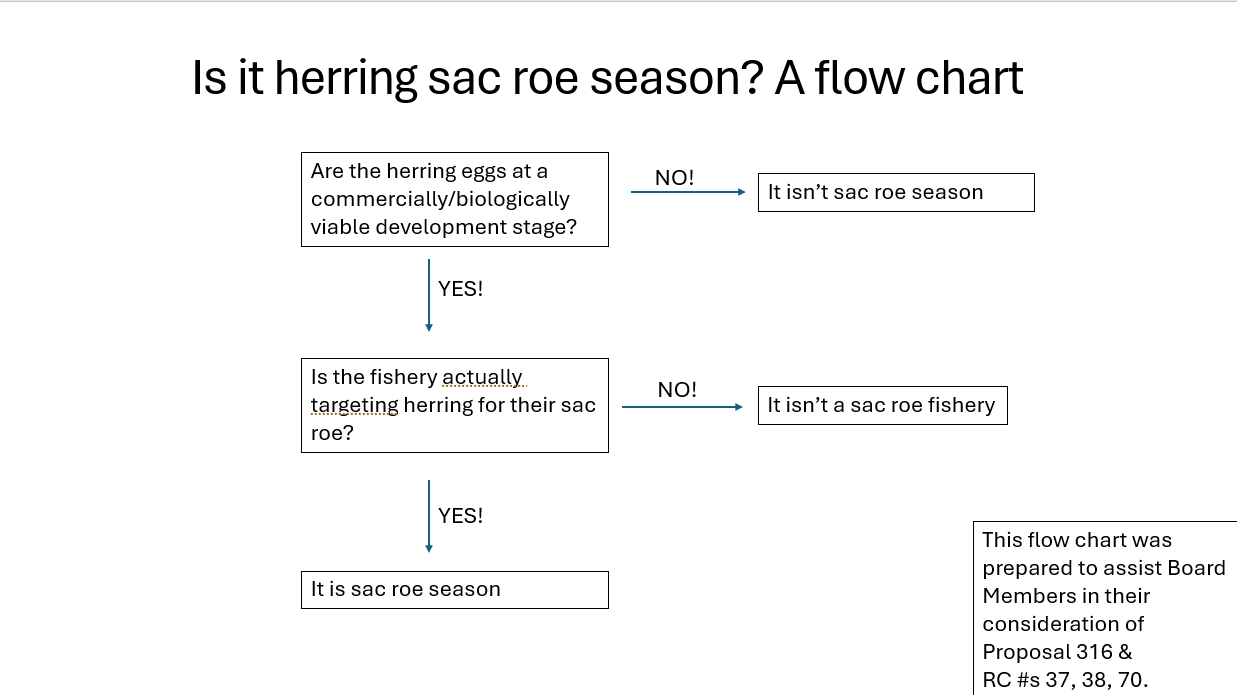

The final passed proposal gives sac roe permit holders in Kodiak the exclusive right to fish on herring for 11 months of the year, which will open up the possibility of making food and reduction products from herring throughout the year there. In the end, to do so, they needed to exploit a maddeningly dumb regulatory loophole: no matter what time of year the sac roe permit holders fish, it will be called a "herring sac roe season". They needed to do that in order to keep everybody else - everybody who doesn't have a sac roe permit - out. It doesn't matter that herring aren't directing their energy towards reproduction in late summer and fall, and it doesn't matter if those permit holders aren't targeting herring for their sac roe; if those guys want to fish, it's herring sac roe season, the regulations now say. I submitted the following flow chart as Record Comment #74, but I guess it didn't move the dial.

Next Up: Responsible Fisheries Management Certification

Ever since the Herring Revitalization Committee lifted off, I've gotten into the habit of checking on the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute every few months to see what kind of progress they're making on their herring market development schemes. In the past I've mentioned that one of the things that could end up justifying the killing of many thousands of tons of herring in Alaska would be if ASMI and their partners can secure Global Food Aid subsidies. ASMI exists in part to foster elaborate political networks of demand for products that nobody is asking for, and I'm interested in the work that they're doing in that regard with herring.

Back in December, ASMI had their annual "All Hands On Deck" conference for their board&staff&whoever. The meeting materials are at this link, and the video of the meeting is below. Herring didn't take up very much time, but a few important things came to light and a couple major gestures were made.

At 2:45:00 or so they get into the herring section of the meeting and two guys - Jeff Regnart and the aforementioned Bruce Schactler - both were members of the Herring Revitalization Committee - speak about their respective initiatives.

Bruce Schactler showcases the current canned herring product that ASMI has been developing and talks about how close they are to being able to attract federal subsidies once that certification is in place. He admitted that this prototype product was watery and wasn't made using the right equipment, but he offered it as a proof of concept that labels could be slapped on cans containing commercial herring. He also acknowledged that the new administration might have some impact on this scheme; surely he was right to worry about that, but such impacts are not the subject of this scrap.

Jeff Regnart talks about his recent work towards getting Responsible Fisheries Management (RFM) certification lined up for Alaska herring, and how the industry is a $60,000 spend and a 6-12 month wait away from securing that certification. I'd imagine this is an easy task for him, since he works as the Program Manager for RFM. You can find the RFM certification standards - which are as watery as Bruce Schactler's canned herring product - here.

The ASMI board then went ahead and voted to fund the $60,000 outlay to get Regnart to move ahead with getting Alaska herring certified as a responsibly managed fish.

How things look from here – it sounds like the certification and the product could both be lined up and ready for subsidized markets, if they exist, towards the end of 2025.

That just about empties the notebook for this stuff. It was a month of meetings that made me feel like herring fisheries are kind of like the show Whose Line is It Anyway?, where everything's made up and the points (of concern) don't matter.