Herring Scrap 25: Impressions of a Season in Sitka

... about herring spawning season as I witnessed it this year in Sitka...

It's been a while since you've heard from me - I fell off the herring scraps habit during my time in Sitka this winter and since then I've just been taken away by summertime.

But this scrap has been perched precariously at the outflow of the scrap machine for months now, and I have a few other half-scraps to pick up on and a bunch more I'd like to conjure, and so... maybe I'll post this one and go from there. You might notice a change - emails are now coming from a platform called Ghost rather than Substack. Same kinda deal. Now that the platform switch is out of the way, all of the posts can be conveniently found and shared at www.herringscraps.com.

I hope to better promote these bits of writing as I try to evolve this project into something that may be more publicly useful - I think that there's going to be a lot of change for herring governance in Alaska in the next year, and I'm worried it will take people by surprise.

But today, a few months behind schedule, I'll show&tell you a bit about spawning season as I witnessed it this year, wandering around Sitka in March and April and bopping around in low-powered boats, taking pictures at mostly the wrong moments, receiving information by manifesting happenstance opportunism at the human-herring interface, maybe kind of like Lawrence Kolloen in 1940, but with access to the internet.

If I have my story straight, and depending how you count it, this was the seventh or ninth time I’ve been more-or-less around for the late-winter/spring herringtime in Sitka. On average over those years, the quality of my attention to the on-the-water doings of herring has been sporadic, haphazard, and under-powered; this year beat the average, just. Maybe I was a bit more shore-bound than I would have liked, but still I got out on the water every few days one way or another and also expended considerable effort on unstructured bicycle&foot surveys of accessible shoreline. And even though I was only an unreliable photographer with standard equipment, I’m here to share with you those photos that I’ve got, and to offer some impressions.

[does a whale impression]

– of a glorious season in Sitka, I mean.

Photos from Brent's Beach cabin, March '24. Morning sun over Sitka Sound; newly-woke bear-prints on the beach; whales blowing.

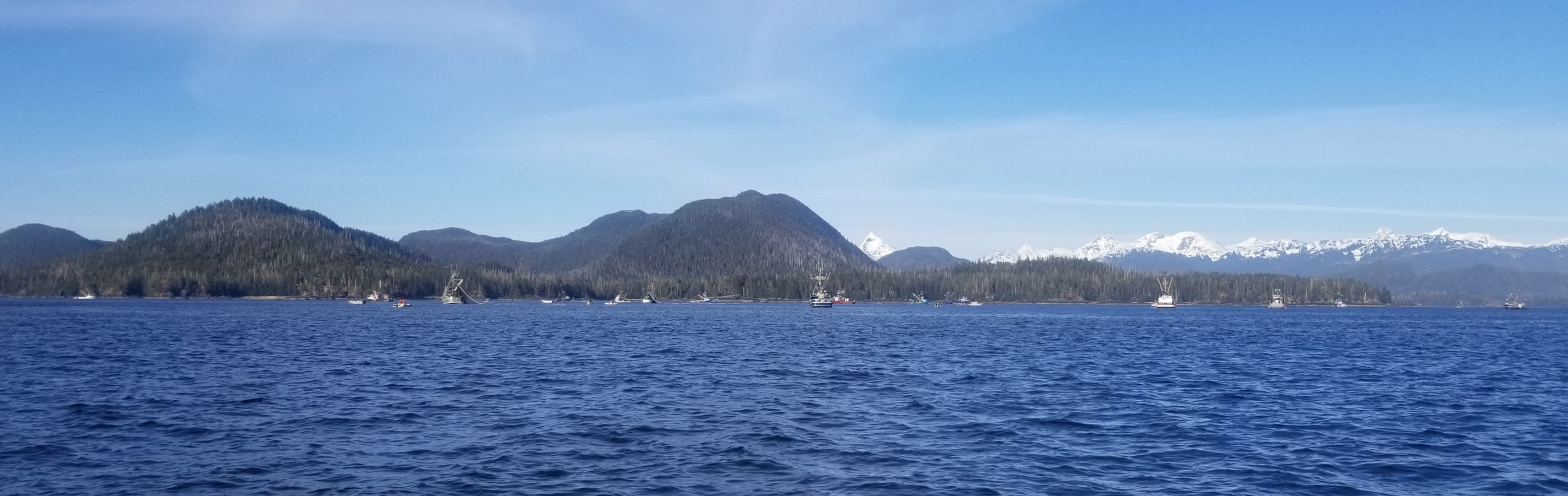

Back in March I booked a cabin on Kruzof Island in hopes that the timing would be right to catch the first herring spawn of the season; instead, we had front row seats on the first days of the commercial fishery while the spawn started up right by town. Whales - mostly humpbacks, at that point in the season - were everywhere in the mornings, plying Hayward Strait and the Kruzof shoreline, until the seiners showed up at 8 or 9, and then - vamoose! Whether because of engine noise or soundings or big nets or basic bad vibes, the whales were gone for the day just about as soon as the boats arrived. It was striking to watch it happen. By late morning, whale parties were firmly displaced by panoramic seining activity like this:

Meanwhile, the spawn had started up in town. These photos are from along the road system as things took off in the last week of March:

Apres-spawn carnage and sunset at Sandy Beach

I was glad to see spawny goings-on along the road system north of town so early in the season, especially in the area known as the closed area. In recent years, an area of near-town spawning grounds has become closed to commercial herring fishing (here’s a link to a .pdf map of the closed area if you want it). That area was established in three parts over the course of several years - a small federally regulated area was closed to commercial use around the airport/causeway, and additional adjacent area was closed by the Board of Fish in 2012 and 2018. Those closures were partial responses to the challenges experienced by subsistence users, and the need for undisturbed spawning grounds within small-boat range of town.

This year, that closed area was lit up with spawn before the rest of Sitka Sound, with something like 22 of the first 45 miles of reported Sitka area spawning happening in that area according to ADF&G surveys. I know that some of those miles yielded some awesomely egg-laden hemlock branches. It’s good to see the closed area respond to being closed. One would expect that a traditionally reliable area of herring spawning grounds will continue to do reliably well if those areas are not fished upon and those spawning grounds are left undisturbed by commercial fishing pressure (it helps to also be spared events like diesel spills; I've written elsewhere that I believe evidence suggests that a 2017 diesel spill in Starrigavan Bay may have had an effect on herring spawning behavior in the following years; certainly there was less spawning in the closed area than ever before in 2018 and 2019).

After spawning had been going on for several days already, I made it out at last for a first kayak paddle of the season. No fuel, no gear, no easy access anywhere: my kind of boat. I noodled out along the shore, visited the minor horde of surfing gulls at Sandy Beach, and then crossed the channel to poke around the Kasiana island group which has long been one of the most reliable places to collect herring roe on branches and kelp. In Herring Synthesis, lifetime subsistence harvester Charlie Skultka said “And when you get in here, say Middle Island, Kasiana Island, those two, they seem to hit virtually every year.” And indeed, that’s where the spawning kicked off this year in Sitka Sound, and that’s where my merry paddle took me.

The paddle starting with this scene away from shore, atop kelp forest south of Kasiana Island, amid a fine chorus of gulls whose richly croaksome wails are attenuated by gulletfulls of herring eggs and the pleasure thereof. The sound of the gulls reminded me of this description from a study by Inspector Ernest Walker of the US Dept of Commerce in 1915. Walker had been sent to investigate the relative impacts of enemies of herring, and his reporting on birds is colorful:

"During the spawning season these vast voracious flocks feed almost exclusively on

the eggs of the herring. At Craig 19 birds were collected and their stomachs examined to ascertain the contents. Of this number there were only three not gorged to their utmost capacity with the eggs, from the crop to the pylorus, and usually even the mouth was full to overflowing. In only one or two cases were there fish in the stomach, and these had probably been picked up dead on the beach when the birds were after eggs. Some of the stomachs contained small quantities of miscellaneous marine matter, but this was probably picked up by accident in the search for eggs."

Ghostly beckonings of deep, roe laden fronds, farther and closer

It took me a few days after that initial spawn for me to get out there by kayak; by then, signs of herring spawn were everywhere, and kelp beds a couple hundred yards from shore were laden with spawn as seen above, much more heavily laden, deeper.

Back on shore, my bicycle surveys kept returning me to Halibut Point Rec and Magic Island (indicated with the marker on the map below, just NE of Kasiana Islands), as well as to Sandy Beach. Especially along Halibut Point Rec, herring eggs were accessibly draped along road system coastline quite thickly!

These photos are from April 11, a week after my paddle and 10 days or more since first spawn; in the first photo of a clump of eggs on my fingertip, you can see that most of the eggs are "eyed" at that point and some appear hatched.

I took this video on a paddle from somewhere around Battery Island on April 20th, with all manner of larval herring life and roe flotsam and planktonic entourage murking the waters– such was the state of things from the boat harbor to whiting harbor that day. This is not a 2024-quality video and may induce seasickness, beware and apologies, you might not find it worth it.

Meanwhile, I caught this brigade cruising through Eliason Harbor on April 20th:

By the time I returned to HPR rec on April 25th, the wind-roes on the beach were crisply sundried, and though the water was still aswirl with eggy remnants, the herring had mostly spawned out, dispersed, moved on. Most survived, many died; their eggs hatched, rotted, eaten, dried. Many meals were made. It was good.

But how good? The season took place in the context of ADF&G claims that it was the biggest herring biomass in Sitka in decades. As I'll point out in a post to follow, ADF&G is so impressed by the numbers that they're coming up with in their fish counts that they're speculating that those numbers mean that the ocean carrying capacity has changed (which, far be it from me to say that the ocean carrying capacity hasn't changed, but certainly I think that the very human herring-counting program in Sitka has changed more than the ocean in the last half-century).

And so I had that in mind - this year as in recent years - as I went about my springtime days in Sitka: is this what a record year should feel like? Is this what an extraordinary herring presence feels like? Or is this just something a little closer to what I hear about when elders speak on the subject, what I read about in Herring Synthesis, in old newspaper articles and in archived reports.

I didn't and don't have an answer except to say that, for my own personal lo-fi herring palpability index, it didn't top 2021 and didn't vastly exceed 2015 and doesn't sound quite as epic as what I've read and heard about... Buuuuuuuutwhatdoiknow? I've only barely seen a bit of it and I get my information from the birds.

Peter

P.S. Upcoming scraps:

Maybe if I say it here it'll make it more likely to come true:

The Board of Fisheries meetings pertaining to Sitka herring are coming up in Ketchikan at the end of January. Due to the uncertain role of the State-led Herring Revitalization Committee (as I wrote about in HS23), this year's meeting is poised to be especially weird, confusing, and, for better or worse, transformative. I'll try to get a post or two out that might help some make sense of all that.

Also, ADF&G has just published a fabulously irritating report re-calculating their average "Unfished Biomass" figure for Sitka Sound. The number is supposed to represent the average size of the spawning herring population in Sitka Sound, simulated for 30,000 years absent fishing pressure. The number they came up with, however, is lower than they have assessed to have been present for 13 of the last 20 years. Hmmmmmmm. More on that soon.