Herring Scrap 22

OR Swim Bladders of The Sky

Since you heard from me last, I arrived back in Sitka, just a day too late to go skating when the conditions were right; I participated in Alaska’s largest ever pinball tournament!1 I started a few new jobs and giglets all at once and have been getting my bearings. The scrap machine has barely been reassembled and certainly hasn’t been tested and cleared for use. But I have to start somewhere, and it’s going to be with a couple more deep-cut archival detours.

I used to collect (vinyl) records. Now I visit archives.

“Check out this primitive Lawrence Kolloen herring biomass chart I took a photo of at the archives…” [says me]

“…. Whooooaaaaaa…..” [says nobody, usually]

Archive truffling is a slightly lonelier pursuit than crate digging, but the rewards are at least as satisfying, at least sometimes.

Those last couple scraps about Lawrence Kolloen’s observations featured things that I found in the U.S National Archives which I haven’t seen quoted or cited anywhere else; old information that hasn’t been read against the new in a very long time. Re-reading Kolloen helps (me) establish the incongruity between varied well documented observational accounts2 and the pseudo-scientific numerical hodgepodge of spreadsheet fantasias deployed by ADF&G to explain the history of herring in Sitka.

All that to say that I find it illuminating to put these generational paradigms of knowledge-making into dialogue. As I learn of collections and documents of interest (not just herring stuff, I swear) in faraway archives, I maintain a disorderly log, organized by city and then by archive and then by collection or document, in case I’m ever near.

I love visiting these spots. Previously, I’d been to the National Archives at College Park (Washington DC) a couple times for the older history of herring fishing (1882-~1920, under the Department of Commerce), as well as at Sand Point (Seattle) for the years under US Fish and Wildlife Service (which yielded Kolloen’s notes, as well as those of his herring research predecessor and successor, George Rounsefell and Bernard Skud).

The National Archive routine is like this: I walk in, admit that I’ve forgotten my researcher card, do the requisite security and training orientation quizlet, go to the research room, find the finding aid binder, compare the reference numbers that I’ve brought (from searches on archives.gov) to the finding aid, fill out a pull slip for the first set of boxes (up to 20, i think) that I’m interested in, and while waiting for that request to be filled, I browse the finding aid binder associated with whatever I’ve requested and discover all of the other things that might have something of interest for me. I get my next pull request form ready. Around that time the door opens and a cart full of papers from times past is wheeled out just for me.

One box at a time, one folder at a time, one file at a time, I move through the boxes as quick as I can without committing archival malfeasance, photographing anything that I might regret not photographing otherwise, leaving annotative breadcrumbs for my future self to deal with at a future time.

I’ve done this a few times now and at this point, I don’t think I need any more herring content from the U.S National Archives. But, like a Winnebago operator with a checklist of National Parks stuck to their fridge, wants exceed needs and I’ll surely get to all of the National Archives eventually.

It was in that spirit that I recently spent a day at the San Bruno, California branch of the National Archives. I knew that they had collections relating to the management of fishing production under the War Production Board during World War II, and that was enough to draw me in. I imagined there could be some weird bundle of telegrams about Sitka herring in wartime (Sitka area was highly militarized in the 1940s), but that wasn’t going to happen: there was nothing about Alaska there (for that I’ll have to return to Seattle). But still I spent an afternoon there at San Bruno, filter-fed through twenty-some boxes full of folders and folders of banal wartime fish stuff, poked through other finding aids, and in the end two finds made the trip feel worthwhile: a pair of particularly illustrative accounts of the steadily increasing political and technological practicability of finding fish to count fish to (commercially) capture fish, over time.

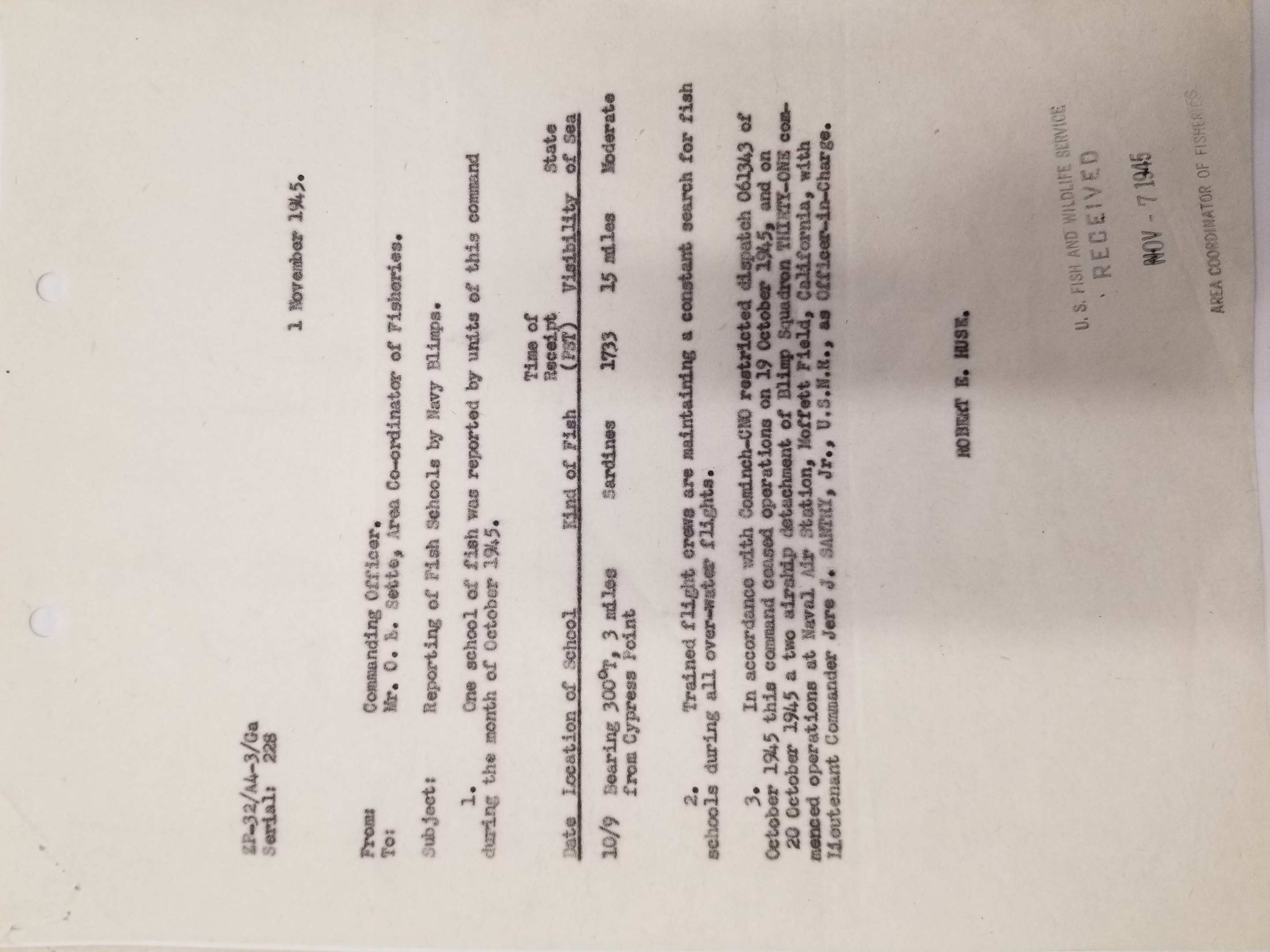

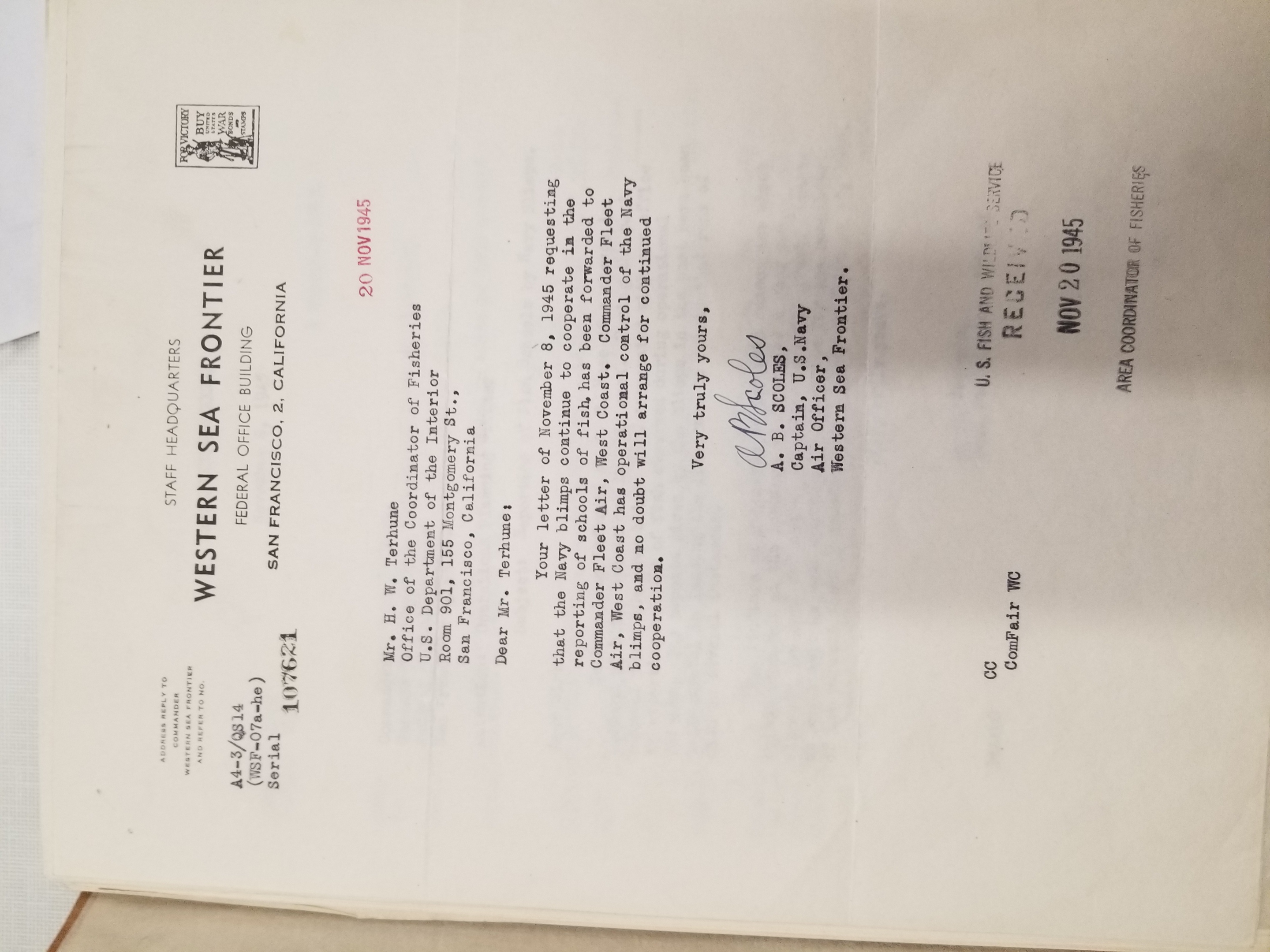

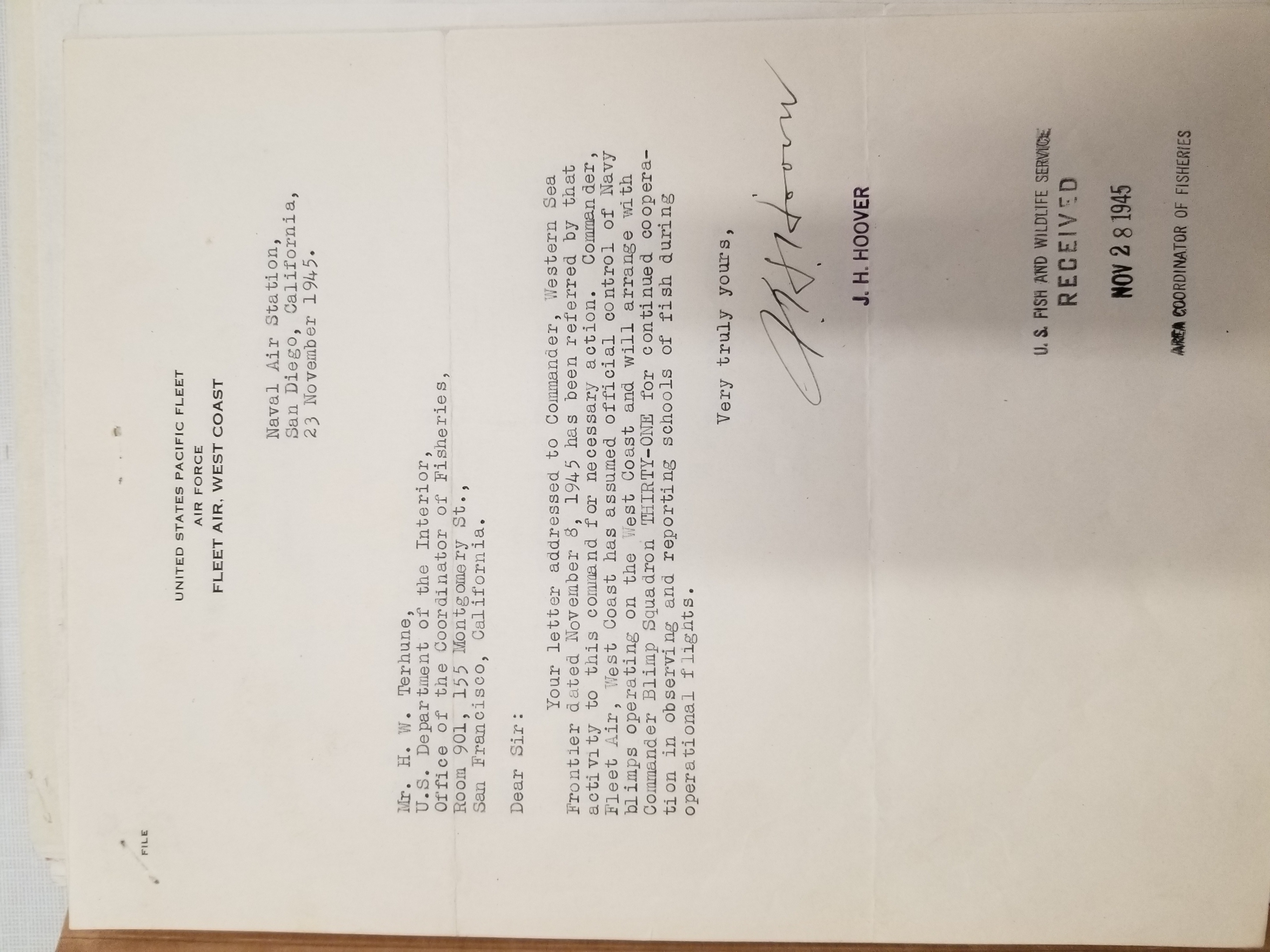

The first bundle of memos come from a folder marked Naval Restrictions - Western Sea Frontier, from one of the containers of General Correspondence from the US F&WS Office of the Area Coordinator of Fisheries Administrative Records, 1942-1946. The documents that caught my imagination were the ones describing the use of military blimps to locate fish for industry off the California coast: a lucid vision from a different time. I’ll share those with you below.

The second came from a folder marked Location of Fish By Sonic Depth-Finder: a set of memos from 1944 appreciating the impending use of military depthfinding equipment for commercial use in fishing, and the possible role for government in demonstrating their effective use by going out and finding fish for the fleet. I won’t return to those today but will circle back before too too long, probably.

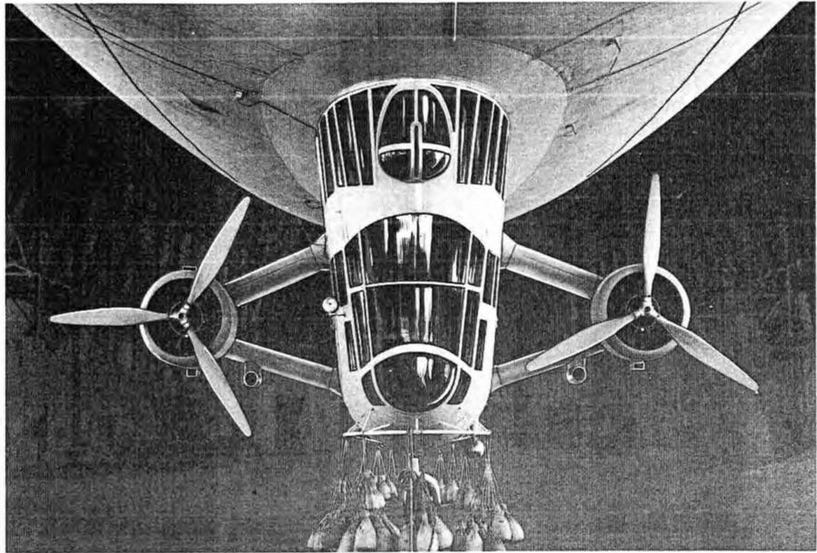

Ok, so blimps.

The U.S. Navy deployed airships armed with radar and depth charges for anti-submarine warfare during the Second World War. It seems they were effective. What I found in that Naval Restrictions - Western Sea Frontier folder was that for “several years” the airships reported “schools of fish observed during operational flights” to the Office of the Coordinator of Fisheries for the US Department of the Interior. I guess I think it’s kind of cute.

Here’s the set of memos:

Four memos about navy blimps "maintaining a constant search for fish schools during all over-water flights", November 1945

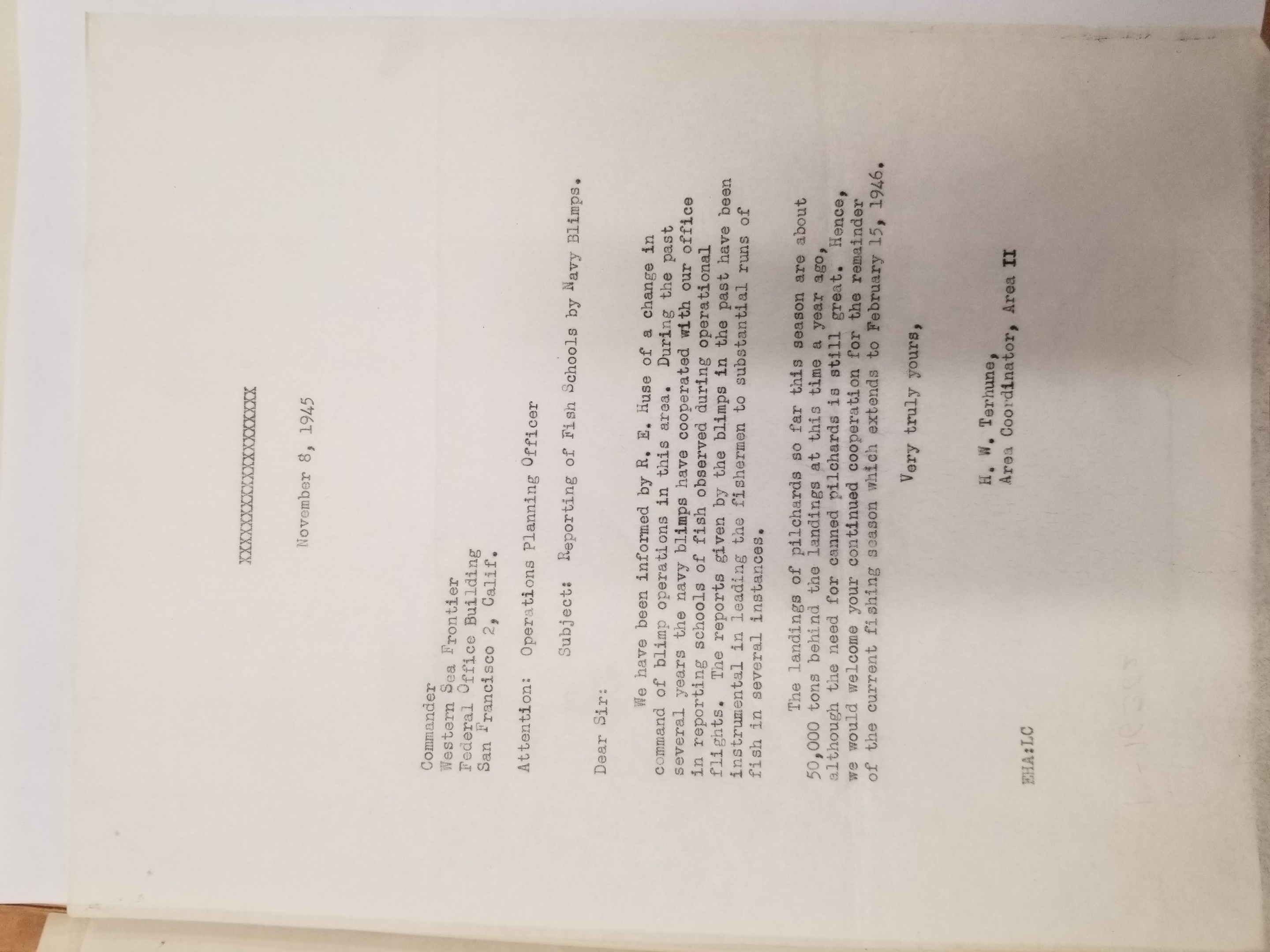

As the airship service deflated in the months after the war, the command responsible for blimps changed, and the Area II Coordinator H.W Terhune worried that blimp intelligence (“The reports given by the blimps in the past have been instrumental in leading the fishermen to substantial runs of fish in several instances.”) might cease and urged the extension of the program: “The landings of pilchards so far this season are about 50,000 tons behind the landings at this time a year ago, although the need for canned pilchards is still great. Hence, we would welcome your continued cooperation for the remainder of the current fishing season which extends to February 15, 1946.”. His request was well received at Western Sea Frontier and then by the Commander of Fleet Air, West Coast, J.H. Hoover. Fish-spotting by navy blimp, presumably, carried on at least for a year or two, though I located no further trace of the doings.

I’ll leave you here with the opening words to the fabulous All The Boats On The Ocean by fisheries historian Carmel Finley (and then, after that, some pictures of k-class blimps like those that might have done the sardine-spotting):

Fishing has always been about much more than just catching fish. Fishing is one of the imperial strategies that nation states employed as they struggled for ocean supremacy. Being a seafaring empire required a range of enterprises and fishing was often just a step toward securing other, more desirable objectives. Hugo Grotius was trying to expand the Dutch empire when he wrote The Free Sea in 1609. The concept of the Freedom of the Sea has been useful to empires ever since. It made world trade profitable. And in the twentieth century, it was central to the rapid postwar expansion of fishing from a coastal, inshore activity to a global enterprise - one that has been so technologically successful there is literally no place left in the oceans for fish to hide.

Mine was a middle-of-the-pack performance. I should have practiced beforehand. I think I ended up playing on 9 or 10 tables. I did great on the Game of Thrones table, ok on Twilight Zone and Terminator, kinda badly on the others. I think I learned some things about effective pinballing though, and so watch out next time. ↩

Not just of Kolloen - My general impression of the common observational record is of a general declining trend from the 1920’s into the 1970’s, and then from early 1990’s until a few years ago. For more observational accounts, see, for example, Herring and People of the North Pacific and Herring Synthesis. ↩