Herring Scrap 31 - Buffalroe Biomasstrology

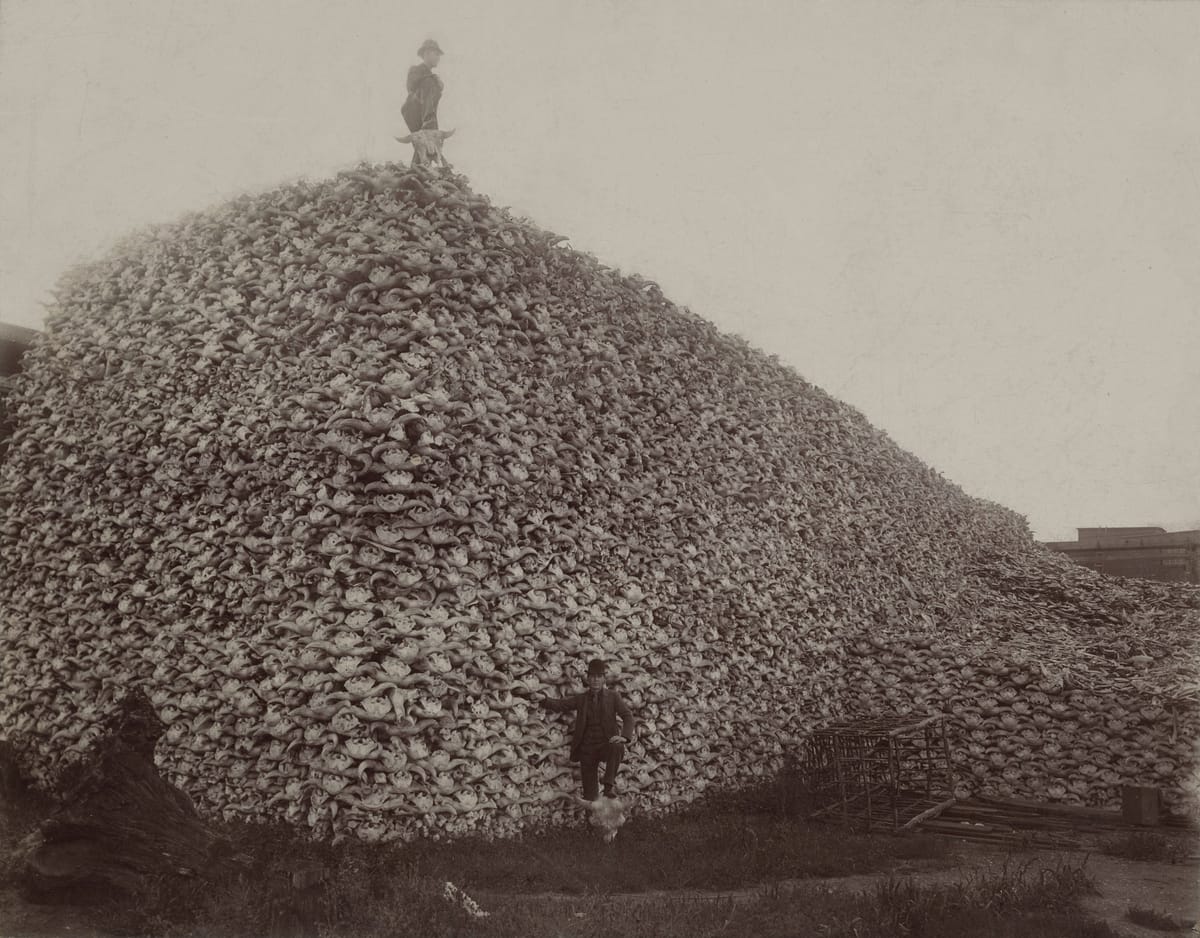

The other day I was poking around in a bookstore and I spotted John Williams' novel Butcher's Crossing (1960), a grisly novel depicting an 1870's buffalo hunt. A young academic from the east coast travels west, inspired by Emerson, looking for a connection to nature, itching to get in on the late-stage buffalo hunt. He stumbles into a tip about a last great herd of buffalo in a hidden valley, and ends up bankrolling a hunt after enlisting a trio of mercenary pioneers.

They find the buffalo; they entrap them; they slaughter them, all of them, almost; they get trapped by winter, hindered by their plunder and ambition. By the time they get back to town, the bottom of the market had dropped out, it was all for naught. Maybe the moral of it is: you can't slaughter your way into good relations. Or maybe it's: if you have money and a yearning, you can do whatever you want and come out alive. I don't quite remember. It's been awhile since I read it. But that's the book. It's not a book on every shelf, and I was surprised and happy to see it there.

It's a book that has flitted across my mind from time to time since I read it a few years ago. I think of it sometimes as I think of the obsessive fisheries management quest to better count herring in order to rationalize higher levels of slaughter. The stronger the counting effort, the bigger the number, the higher the possible kill. And so when I saw Butcher's Crossing on the bookshelf, my mind got to thinking about buffalo and herring, counting and slaughter, and the limits and rewards of metaphor. Also, stars.

A few days later, home again, I pulled my dusty copy of Butcher's Crossing off the shelf. I wanted to go back and find the parts where the characters assess buffalo numbers:

Early in the book, Miller (a seasoned buffalo hunter) pitches Andrews (the young east coaster looking for an adventure) on the idea of going up to this hidden mountain valley full of buffalo, and he recounts the time he visited the valley 10 years prior:

"I followed the bed up the mountain the rest of that day, and near nightfall come out on a valley bed flat as a lake. That valley wound in and out of the mountains as far as you could see; and they was buffalo scattered all over it, in little herds, as far as a man could see. Fall fur, but thicker and better than winter fur on the plains grazers. From where I stood, I figured maybe three, four thousand head; and they was more around the bends of the valley I couldn't see."

Miller convinces Andrews to bankroll the hunt based on what he'd assessed ten years prior. The math of the proposition unwinds from there. Andrews is convinced - it sounds like an interesting way to connect with nature and with that much buffalo the money surely can't help but work out. They embark, eventually arriving at the valley and getting their first sight of the buffalo:

Miller tensed, and touched Andrews' arm. "Look!" He pointed to the southwest.

A blackness moved on the valley, below the dark pines that grew on the opposite mountain. Andrews strained his eyes; at the edges of the patch, there was a slight ripple; and then the patch itself throbbed like a great body of water moved by obscure currents. The patch, though it appeared small at this distance, was, Andrews guessed, more than a mile in lenth and nearly a half mile in width.

"Buffalo," Miller whispered.

"My God!" Andrews said. "How many are there?"

"Two, three thousand maybe. And maybe more. This valley winds in and out of these hills; we can just see a little part of it from here. No telling what you'll find on farther."

For several moments more, Andrews stood beside Miller and watched the herd. He could, at the distance from which he viewed, make out no shape, distinguish no animal from another.

The hunt begins. The days pass, time is measured by the size of the herd, and the target harvest rate clarifies:

Gradually the herd was worn down. Everywhere he looked Andrews saw the ground littered with naked corpses of buffalo, which sent up a rancid stench to which he had become so used that he hardly was aware of it; and the remaining herd wandered placidly among the ruins of their fellows, nibbling at grass flecked with their dry brown blood. With his awareness of the diminishing size of the herd, there came to Andrews a realization that he had not contemplated the day when the herd was finally reduced to nothing, when not a buffalo remained standing - for unlike Schneider he had known, without questioning or without knowing how he knew, that Miller would not willingly leave the valley so long as a single buffalo remained alive. He had measured time, and had reckoned the moment and place of their leaving, by the size of the herd, and not - as had Schneider - by numbered days that rolled meaninglessly one after another.

Some days later, all of the numbers start to become more precise, the numbers of bison both dead and alive clarified as they hunted and prepared hides, and the animals become individualized in the eyes of the men as the work loses steam.

On their twenty-fifth day in the mountains they arose late. For the last several days, the slaughter had been going more slowly; the great herd, after more than three weeks, seemed to have begun to realize the presence of their killers and to have started dumbly to prepare against them; they began to break up into a number of very small herds; seldom was Miller able to get more than twelve or fourteen buffalo at a stand, and much time was wasted in traveling from one herd to another. But the earlier sense of urgency was gone; the herd of some five thousand animals was now less than three hundred. Upon these remaining three hundred, Miller closed in - slowly, inexorably - as if more intensely savoring the slaughter of each animal as the size of the herd diminished. On the twenty-fifth day they arose without hurry; and after they had taken breakfast they even sat around the fire for several moments letting their coffee cool in their tin cups.

It's a really pretty grim novel about the scale of rationalized imposition that can be done someplace in short order by men experimenting with power, detached from consequence. Counting was enacted; ownership was asserted; the creatures got killed; the money worked out; the protagonist emerged unscathed: that's biomass assessment for you.

In Butcher's Crossing, the numeric thinking about the bison crystalizes as the men engage more closely with the buffalo through slaughter. By the time they finish their work in the valley, they have a very good sense of how many bison were in the valley when they arrived and how many were left upon their departure. In these last scraps, I've been trying to illustrate: this is not how it works with herring. And in thinking about counting buffalo while killing buffalo, or counting herring in order to rationalize killing herring, I was trying to think of something else that people try to count, at great effort, against all odds of getting it right. Something that you can't possibly pull it off without a big foundation of assumptions and tools and resources and team and technology, but you can sure try and if you do you'll surely get better at it with time? Buffalo or salmon: too easy to count. Maybe monarch butterflies, or bats, or lightning strikes. But I got to thinking about stars, the counting and cataloguing of stars, and the layered foundation of knowledge and deep reach into the unknown required to count stars, and I thought: stars works.

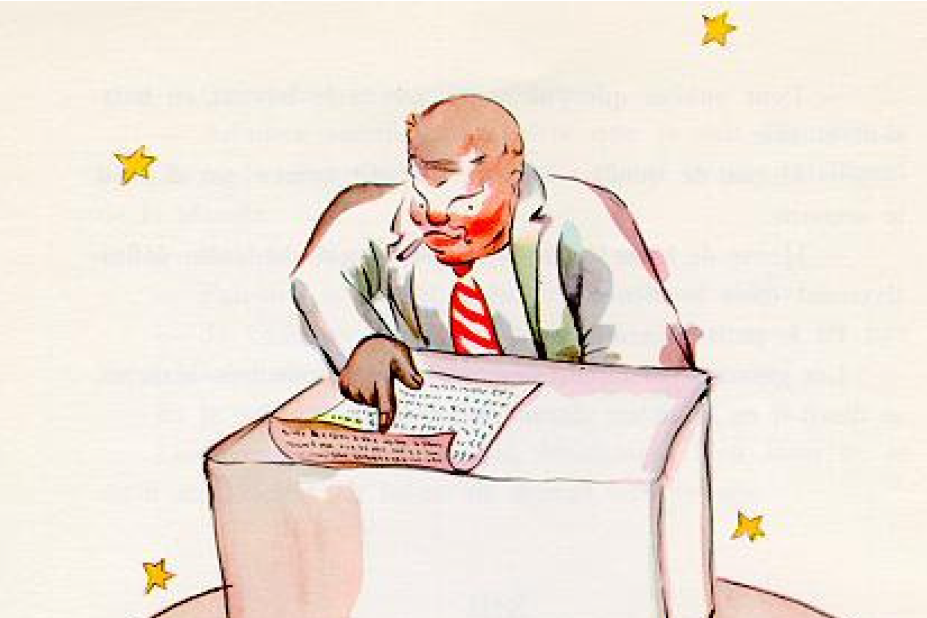

Do you know The Little Prince?

Chapter 13, and The Little Prince shows up on a planet and meets the sole resident, The Businessman. The Businessman is counting ("Five-hundred-and-one million--I can't stop . . . I have so much to do! I am concerned with matters of consequence. I don't amuse myself with balderdash.") when little prince walks in. Little prince badgers him about what he's counting until he answers:

"Millions of what?"

The businessman suddenly realized that there was no hope of being left in peace until he answered this question.

"Millions of those little objects," he said, "which one sometimes sees in the sky."

"Flies?"

"Oh, no. Little glittering objects."

"Bees?"

"Oh, no. Little golden objects that set lazy men to idle dreaming. As for me, I am concerned with matters of consequence. There is no time for idle dreaming in my life."

"Ah! You mean the stars?"

"Yes, that's it. The stars."

"And what do you do with five-hundred millions of stars?"

"Five-hundred-and-one million, six-hundred-twenty-two thousand, seven-hundred-thirty-one. I am concerned with matters of consequence: I am accurate."

"And what do you do with these stars?"

"What do I do with them?"

"Yes."

"Nothing. I own them."

"You own the stars?"

"Yes."

There's surely a spectrum of models for enumeration as an ownership claim, and somewhere on that spectrum is the model deployed by The Businessman in The Little Prince and somewhere on it is the model deployed by Andrews and Miller in Butcher's Crossing. Somewhere between the two, I think, would be the way that limited-entry herring-permit ownership is enacted in Alaska.

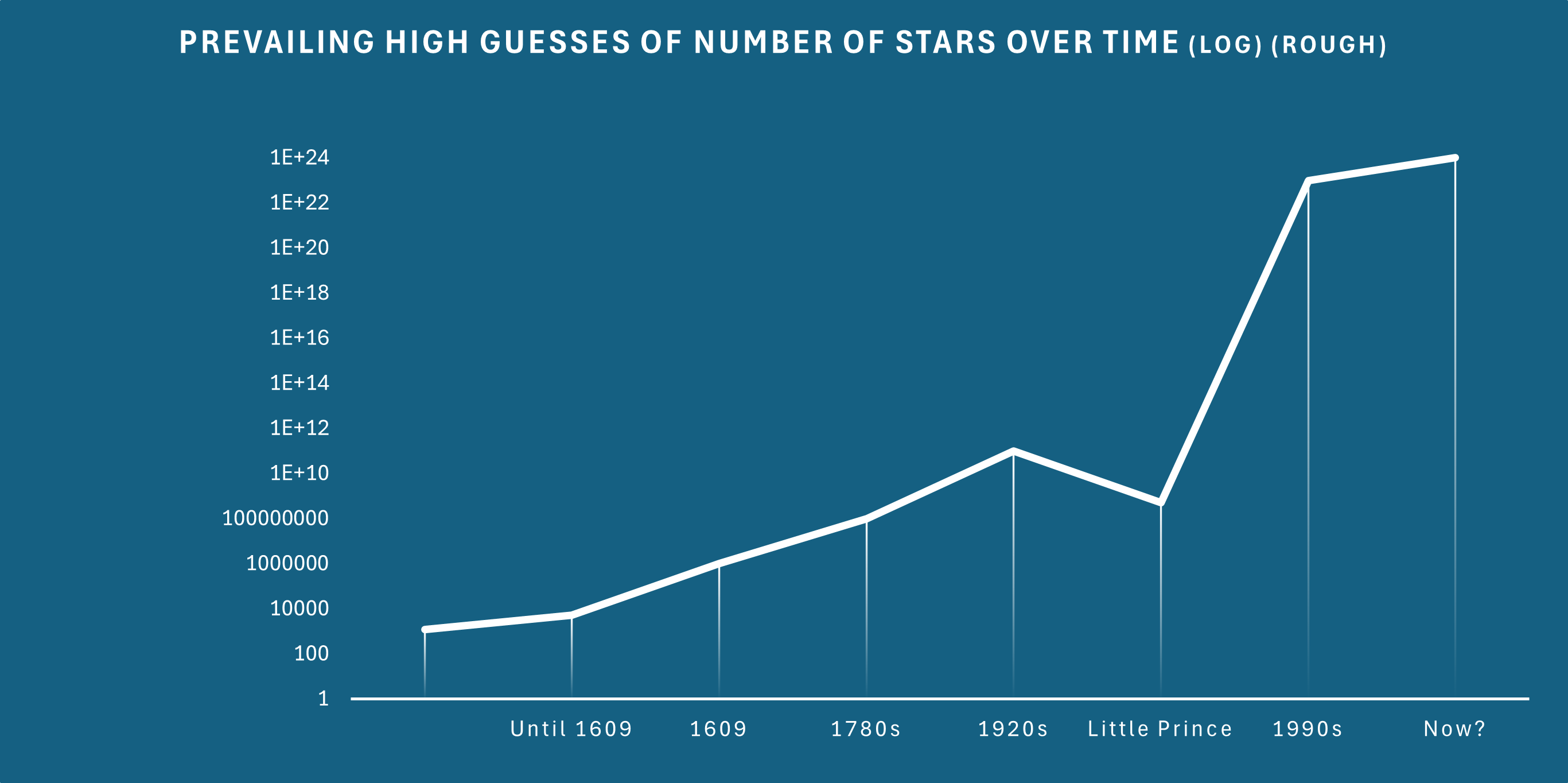

And so what about stars? What has it been like, over time, the quest to imagine the number of stars out there. Has it been sort of like the quest to know the number of herring?

I am concerned with matters of consequence.

I consulted the internet and was surprised that I couldn't immediately find the chart I was looking for: star counts over time. So the internet and I co-researched the question for a few minutes, mocked up some low-quality research, charted a few points on a log scale, and voila:

Behold, the extraordinary expansion in our concept of the Universal astral inventory. Look at how our star-counting has changed! We used to be so under-prepared to count stars but look at us now! One septillion stars! Dang! This chart marks the rise from ancient indexes of identified stars to Galileo's telescope, through expansions in technique and technology, through Hubble's discoveries in the 1920's, with a dip in 1945 to accommodate the lower-than-contemporary-norms estimate in The Little Prince, and a really extraordinary expansion in starquanting since. I really want to stress that the above chart is not serious and precise research, but is, I think, enough to demonstrate a notion:

I think it's safe to say that the entirety of the recent (415 years) movement in the graph on star counting can be attributed to the layered process of learning how to count stars, and not to some extraordinary bloom of new stars.

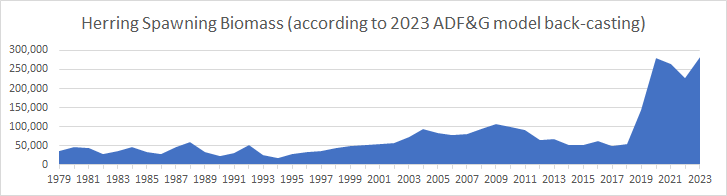

Please join me now in a metaphoric leap. Without getting too lost in the details — doesn't the above star-chart follow a similar sort of contour to the herring biomass chart below, a little bit, don't you think?

And so I wonder - and I thank you for taking the time to wonder about this here, with me - how much of ADF&G's trend in biomass over the course of the time series can be attributed to real extraordinary herring population increase, and how much is best attributed to the process of learning how to model herring populations based on egg deposition across a vast area?

An open question.

Peter